PermalinkIntroduction

In the world of software development, testing plays a vital role in ensuring the reliability and stability of our applications. When writing tests, we often come across situations where certain dependencies need to be simulated or replaced to isolate the behavior of the code under test. This is where Test Doubles come into play.

Test Doubles, also known as Test Fakes or Test Stubs, are powerful techniques used to create substitutes for collaborating objects in our tests. These substitutes allow us to control the behavior of these dependencies, facilitating focused and reliable testing. In the context of Go programming, Test Doubles provide a way to enhance the effectiveness of our unit tests and improve the overall quality of our software.

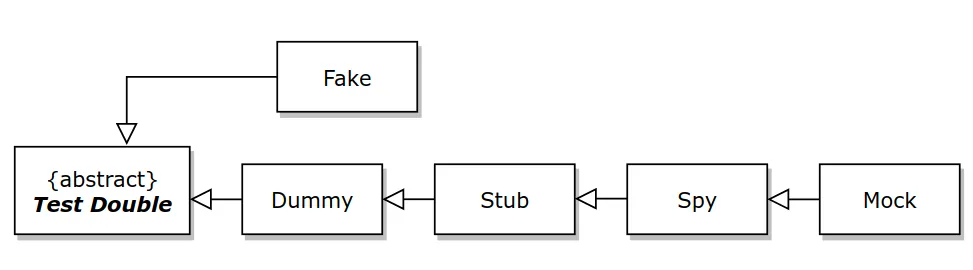

PermalinkThe five types of Test Doubles are:

Dummy: It is used as a placeholder when an argument needs to be filled in.

Stub: It provides fake data to the SUT (System Under Test).

Spy: It records information about how the class is being used.

Mock: It defines an expectation of how it will be used. It will cause failure if the expectation isn’t met.

Fake: It is an actual implementation of the contract but is unsuitable for production.

PermalinkWhen do we need Test Doubles?

There are several scenarios in which Test Doubles become invaluable. One common use case arises when an application relies on external services, databases, or APIs. Accessing these services during unit testing can introduce dependencies on their availability, performance, or even the data they contain. By employing Test Doubles, we can avoid such dependencies and ensure that our tests remain isolated and predictable.

Another situation where Test Doubles are beneficial is when certain code paths are challenging to reach or when we want to simulate specific conditions that are hard to reproduce in real-world scenarios. For instance, simulating network failures, time-sensitive operations, or exceptional error conditions can be challenging without Test Doubles. They enable us to create controlled environments that simulate these scenarios, allowing us to thoroughly test our code's resilience and edge case handling.

PermalinkWhy use Test Doubles?

The primary motivation behind using Test Doubles is to decouple the code under test from its dependencies, allowing us to test components in isolation. By replacing real objects with Test Doubles, we gain fine-grained control over their behavior, ensuring that our tests focus solely on the unit being tested. This isolation helps identify bugs and regressions more effectively and simplifies the debugging process, as the source of errors can be localized to the specific unit.

Moreover, Test Doubles enable developers to write tests that are more deterministic and repeatable. Instead of relying on the availability and consistency of external services, we can define the exact behavior of the Test Doubles, making our tests more reliable and less prone to false positives or negatives. This predictability leads to faster feedback loops, allowing developers to catch and fix issues early in the development cycle.

In this article series, we will explore different types of Test Doubles in Go: Dummies, Stubs, Spies, Mocks, and Fakes. Each type has its unique characteristics and use cases, empowering us to address a wide range of testing scenarios effectively. By the end of this series, you will have a solid understanding of how to leverage Test Doubles in your Go codebase and take your testing efforts to the next level.

PermalinkDummies

PermalinkWhat are Dummies?

Dummies are the most straightforward form of Test Doubles. They are essentially empty or minimal implementations of objects that are required as method arguments or collaborators but do not contribute to the behavior of the unit under test. Dummies are used solely to satisfy the compiler or fulfill parameter expectations, allowing the test code to execute successfully.

PermalinkWhen to use Dummies?

Dummies are typically employed when a unit under test requires certain objects or parameters but does not actually use them during its execution. Instead of creating complex or fully functional objects, we can use Dummies to fulfill these requirements and ensure the code compiles and runs without raising any errors or exceptions.

PermalinkExample Usage of Dummies

Imagine you have a Logger interface responsible for logging messages, and you want to test a Calculator struct that performs some calculations and logs the results. In this case, you can use a Dummy implementation of the Logger interface to satisfy the dependency without any actual logging:

type Logger interface {

Log(message string)

}

type Calculator struct {

logger Logger

}

func (c *Calculator) Add(a, b int) int {

sum := a + b

c.logger.Log(fmt.Sprintf("Addition: %d + %d = %d", a, b, sum))

return sum

}

In your test scenario, you can create a Dummy implementation of the Logger interface that doesn't perform any logging:

type DummyLogger struct{}

func (d *DummyLogger) Log(message string) {

// Do nothing

}

Now, when testing the Add method of the Calculator, you can use the DummyLogger as a substitute for the Logger dependency:

import (

"testing"

)

func TestCalculator_Add(t *testing.T) {

dummyLogger := &DummyLogger{}

calculator := &Calculator{logger: dummyLogger}

result := calculator.Add(2, 3)

expected := 5

if result != expected {

t.Errorf("Addition result incorrect. Got %d, expected %d", result, expected)

}

}

In this example, the DummyLogger acts as a placeholder that satisfies the Logger dependency without performing any actual logging. It allows you to focus on testing the logic of the Calculator without worrying about the logging functionality.

Using a Dummy in this scenario helps to isolate the unit under test and simplifies the testing process by eliminating the need for a real Logger implementation.

PermalinkStubs

PermalinkWhat are Stubs?

Stubs are Test Doubles that allow us to replace dependencies and control their behavior during testing. Unlike Dummies, which are empty or minimal implementations, Stubs provide predefined responses or behavior when specific methods are invoked. By using Stubs, we can simulate various conditions or scenarios, such as returning specific values, triggering exceptions, or even simulating delays.

PermalinkWhen to use Stubs?

Stubs are particularly useful in situations where our code under test relies on external services, databases, or APIs, which might not be available or desirable to use during testing. By replacing these dependencies with Stubs, we can simulate their behavior and responses, making our tests more isolated and predictable. Stubs also come in handy when we need to test error-handling or exceptional scenarios that are challenging to reproduce consistently in real-world conditions.

PermalinkExample Usage of Stubs

To illustrate the usage of Stubs, let's consider a simplified example where we have a WeatherService interface responsible for retrieving weather data, and a WeatherReporter struct that uses this service to report the current weather condition.

type WeatherService interface {

GetWeather(city string) (string, error)

}

type WeatherReporter struct {

weatherService WeatherService

}

func (wr *WeatherReporter) ReportWeather(city string) string {

weather, err := wr.weatherService.GetWeather(city)

if err != nil {

return "Failed to retrieve weather data."

}

return "Current weather: " + weather

}

In our test scenario, we want to ensure that the ReportWeather method correctly handles the case when the GetWeather method returns an error. We can use a Stub implementation of the WeatherService to simulate this scenario:

import (

"testing"

"errors"

)

type StubWeatherService struct{}

func (sws *StubWeatherService) GetWeather(city string) (string, error) {

return "", errors.New("API error: failed to retrieve weather data")

}

func TestWeatherReporter_ReportWeather_Error(t *testing.T) {

stubService := &StubWeatherService{}

weatherReporter := &WeatherReporter{weatherService: stubService}

result := weatherReporter.ReportWeather("New York")

expected := "Failed to retrieve weather data."

if result != expected {

t.Errorf("ReportWeather returned %q, expected %q", result, expected)

}

}

In the above example, we create a Stub implementation of the WeatherService interface called StubWeatherService. The GetWeather method of the Stub implementation always returns an error. By using this Stub in our test, we simulate the scenario where the weather service fails to retrieve the weather data. We then verify that the ReportWeather method correctly handles this error condition. Stubs are powerful Test Doubles that allow us to replace dependencies and control their behavior during testing. They provide predefined responses or behavior, enabling us to simulate specific scenarios and test various conditions more effectively. By utilizing Stubs, we can isolate our code under test and ensure that it behaves correctly in different scenarios, including error-handling and exceptional cases. In the next part of this series, we will explore another type of Test Double: Spies. Stay tuned to learn how Spies can enhance your Go testing experience.

PermalinkSpies

PermalinkWhat are Spies?

Spies are Test Doubles that serve as proxies for dependencies, allowing us to observe and verify how they are used during testing. Unlike Dummies and Stubs, which focus on parameter requirements or predetermined responses, Spies provide a means to capture information about method invocations, such as the number of calls, arguments passed, or even the order in which methods are called. By using Spies, we gain insights into the interactions between our code under test and its collaborators.

PermalinkWhen to use Spies?

Spies are particularly useful when we want to verify that certain methods or dependencies are invoked correctly or a specific sequence of interactions occurs. They help us ensure that our code under test interacts with its dependencies as expected, leading to more reliable and accurate tests. Spies also allow us to capture and analyze relevant data about method calls, enabling us to perform assertions based on those observations.

PermalinkExample Usage of Spies

To illustrate the usage of Spies, let's consider a simplified example where we have a PaymentGateway interface responsible for processing payment transactions, and a PaymentProcessor struct that uses this gateway to initiate payments.

type PaymentGateway interface {

ProcessPayment(amount float64, currency string) error

}

type PaymentProcessor struct {

paymentGateway PaymentGateway

}

func (pp *PaymentProcessor) MakePayment(amount float64, currency string) error {

return pp.paymentGateway.ProcessPayment(amount, currency)

}

In our test scenario, we want to ensure that the MakePayment method correctly calls the ProcessPayment method on the PaymentGateway. We can use a Spy implementation of the PaymentGateway to capture and verify this interaction:

import (

"testing"

)

type SpyPaymentGateway struct {

processPaymentCalled bool

lastAmount float64

lastCurrency string

}

func (spy *SpyPaymentGateway) ProcessPayment(amount float64, currency string) error {

spy.processPaymentCalled = true

spy.lastAmount = amount

spy.lastCurrency = currency

return nil

}

func TestPaymentProcessor_MakePayment(t *testing.T) {

spyGateway := &SpyPaymentGateway{}

paymentProcessor := &PaymentProcessor{paymentGateway: spyGateway}

amount := 100.0

currency := "USD"

err := paymentProcessor.MakePayment(amount, currency)

if !spyGateway.processPaymentCalled {

t.Error("ProcessPayment not called")

}

if spyGateway.lastAmount != amount {

t.Errorf("ProcessPayment called with amount %f, expected %f", spyGateway.lastAmount, amount)

}

if spyGateway.lastCurrency != currency {

t.Errorf("ProcessPayment called with currency %s, expected %s", spyGateway.lastCurrency, currency)

}

if err != nil {

t.Errorf("MakePayment returned error: %v", err)

}

}

In the above example, we create a Spy implementation of the PaymentGateway interface called SpyPaymentGateway. The Spy records information about the method calls made to it, including the fact that ProcessPayment was called, as well as the amount and currency passed to it. In our test, we verify that the MakePayment method correctly interacts with the PaymentGateway by examining the captured information.

Spies are powerful Test Doubles that allow us to observe and verify interactions between the code under test and its dependencies. They provide insights into method calls, including the number of invocations, arguments passed, and the order in which methods are called. By using Spies, we can ensure that our code interacts correctly with its collaborators and perform assertions based on the captured information.

PermalinkMocks

PermalinkWhat are Mocks?

Mocks are Test Doubles that simulate the behavior of real dependencies, providing us with the ability to define expectations and verify interactions. Unlike Stubs and Spies, which focus on predetermined responses or capturing method calls, Mocks allow us to specify the expected sequence of method calls, parameters, and return values. They enable us to create controlled test scenarios by defining how the dependencies should behave during the test.

PermalinkWhen to use Mocks?

Mocks are particularly useful when we want to thoroughly test the interactions between our code under test and its dependencies. By using Mocks, we can precisely define expectations about the method calls, their parameters, and return values. This level of control allows us to test complex logic, edge cases, and ensure that our code correctly handles various scenarios. Mocks also aid in isolating the unit under test, as we can replace its dependencies with Mocks, preventing unwanted side effects during testing.

PermalinkExample Usage of Mocks

To illustrate the usage of Mocks, let's consider a simplified example where we have a EmailSender interface responsible for sending email notifications, and a UserManager struct that uses this sender to notify users.

type EmailSender interface {

SendEmail(address, subject, body string) error

}

type UserManager struct {

emailSender EmailSender

}

func (um *UserManager) SendWelcomeEmail(email string) error {

subject := "Welcome to our platform!"

body := "Thank you for joining. We're excited to have you on board."

return um.emailSender.SendEmail(email, subject, body)

}

In our test scenario, we want to ensure that the SendWelcomeEmail method correctly calls the SendEmail method on the EmailSender interface. We can use a Mock implementation of the EmailSender to define expectations and verify the interactions:

import (

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/mock"

)

type MockEmailSender struct {

mock.Mock

}

func (mock *MockEmailSender) SendEmail(address, subject, body string) error {

args := mock.Called(address, subject, body)

return args.Error(0)

}

func TestUserManager_SendWelcomeEmail(t *testing.T) {

mockSender := &MockEmailSender{}

userManager := &UserManager{emailSender: mockSender}

email := "test@example.com"

expectedSubject := "Welcome to our platform!"

expectedBody := "Thank you for joining. We're excited to have you on board."

mockSender.On("SendEmail", email, expectedSubject, expectedBody).Return(nil)

err := userManager.SendWelcomeEmail(email)

if err != nil {

t.Errorf("SendWelcomeEmail returned error: %v", err)

}

mockSender.AssertExpectations(t)

}

In the above example, we create a Mock implementation of the EmailSender interface called MockEmailSender. Using the github.com/stretchr/testify/mock package, we define expectations on the SendEmail method with specific parameters. We then use the AssertExpectations method to ensure that all the expectations were met during the test.

PermalinkFakes

PermalinkWhat are Fakes?

Fakes are Test Doubles that provide simplified, alternative implementations of dependencies. They are often used when the real implementation of a dependency is complex, resource-intensive, or not suitable for testing purposes. Fakes aim to simplify the behavior of the dependency, providing a lightweight and controllable substitute. Unlike Stubs and Mocks, which focus on specific method calls and interactions, Fakes provide a full implementation of the dependency, albeit with simpler functionality.

PermalinkWhen to use Fakes?

Fakes are particularly useful when the real implementation of a dependency is impractical or undesirable to use during testing. This can be due to reasons such as network dependencies, external services, or complex business logic. By using Fakes, we can simulate the behavior of the dependency in a controlled manner, making our tests more predictable, isolated, and efficient. Fakes are also helpful when we need to test scenarios that are challenging to reproduce consistently with the real implementation.

PermalinkExample Usage of Fakes

To illustrate the usage of Fakes, let's consider a simplified example where we have a FileStore interface responsible for storing and retrieving files, and a FileManager struct that uses this store to perform file-related operations.

type FileStore interface {

StoreFile(filename string, data []byte) error

RetrieveFile(filename string) ([]byte, error)

}

type FileManager struct {

fileStore FileStore

}

func (fm *FileManager) SaveFile(filename string, data []byte) error {

return fm.fileStore.StoreFile(filename, data)

}

func (fm *FileManager) ReadFile(filename string) ([]byte, error) {

return fm.fileStore.RetrieveFile(filename)

}

In our test scenario, we want to ensure that the FileManager correctly interacts with the FileStore when saving and reading files. We can use a Fake implementation of the FileStore to provide simplified behavior for testing:

import (

"testing"

)

type FakeFileStore struct {

storedFiles map[string][]byte

}

func (fake *FakeFileStore) StoreFile(filename string, data []byte) error {

fake.storedFiles[filename] = data

return nil

}

func (fake *FakeFileStore) RetrieveFile(filename string) ([]byte, error) {

data, exists := fake.storedFiles[filename]

if !exists {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("File not found: %s", filename)

}

return data, nil

}

func TestFileManager_SaveFile_ReadFile(t *testing.T) {

fakeStore := &FakeFileStore{storedFiles: make(map[string][]byte)}

fileManager := &FileManager{fileStore: fakeStore}

// Save file

filename := "test.txt"

data := []byte("Hello, World!")

err := fileManager.SaveFile(filename, data)

if err != nil {

t.Errorf("SaveFile returned error: %v", err)

}

// Read file

retrievedData, err := fileManager.ReadFile(filename)

if err != nil {

t.Errorf("ReadFile returned error: %v", err)

}

if !bytes.Equal(retrievedData, data) {

t.Errorf("Retrieved data does not match expected data")

}

}

In the above example, we create a Fake implementation of the FileStore interface called FakeFileStore. The Fake implementation simplifies the behavior by storing files in memory using a map. During the test, we can save a file using the SaveFile method and retrieve it using the ReadFile method. We can then assert that the retrieved data matches the expected data.

PermalinkBest practices

| Test Double | Purpose | Behavior | Interaction Verification | Internal Behavior Recording | Use Case in Real Projects | Verification |

| Dummy | Placeholder object | Does nothing | No | No | When a parameter is required but not used in the test | Not applicable |

| Stub | Provide predetermined responses | Returns fixed values | No | No | Simulating simple behaviors or reducing dependencies | Not applicable |

| Mock | Set expectations on interactions | Returns predetermined values | Yes | No | Testing how an object interacts with its dependencies | Checks if expected interactions occurred |

| Fake | Alternative simplified implementation | Replicates some real behavior | No | No | Replacing resource-heavy dependencies for faster testing | May not require explicit verification |

| Spy | Record interactions and parameters | Returns actual data but records calls | Yes | No | Observing and recording internal interactions | May be used to assert expected behavior |

| Double | General term for any test substitute | Varies depending on the type of double | Varies depending on the type of double | Varies depending on the type of double | Varied based on the specific type of double used | Verification depends on the specific test double used |

PermalinkKey Characteristics

PermalinkDummy

Provides a valid object to fulfill method signature requirements

Does not affect the test outcome as it's not involved in the test logic

Often used in situations where an argument is necessary but has no impact on the test behavior

PermalinkStub

Returns fixed values or exceptions for method calls

Used when you want to isolate the code from complex external dependencies

Suitable for emulating read-only operations or methods with predictable behaviors

PermalinkMock

Sets expectations on method calls and parameters

Verifies whether specific methods were invoked and how many times

Can throw exceptions based on predefined conditions

Helps in testing interaction patterns and ensuring proper collaboration between objects

PermalinkFake

Provides an alternative implementation of a dependency with simplified functionality

Can be used to replace a slow or resource-intensive component with a lighter, faster version

Often used for databases, file systems, or external services where setting up the real component is impractical or time-consuming

PermalinkSpy

Acts as a wrapper around the real object to monitor method calls and their parameters - Records the interactions and usage patterns during the test

Useful when you want to test both the result and how the result was achieved

Provides insights into how the object under test is used in the application

PermalinkDouble

A general term for any object that substitutes a real dependency in testing

Can refer to dummy, stub, mock, fake, or spy

Enables test isolation and focuses on specific components or behaviors

PermalinkConclusion

In conclusion, the article delves into the concept of Test Doubles and their significance in separating code from dependencies and enabling precise control over behavior during testing. The five types of Test Doubles - Dummies, Stubs, Spies, Mocks, and Fakes - each serve distinct purposes and cater to specific use cases. For instance, Dummies fulfill parameter requirements, Stubs provide predetermined responses, Spies capture method call information, Mocks imitate real dependencies, and Fakes offer simplified alternative implementations. Employing Test Doubles empowers developers to craft more dependable and accurate tests, resulting in faster feedback loops and heightened code quality.

PermalinkContributing

At Dwarves, we encourage our people to read, write, share what we learn with others, and contributing to the Brainery is an important part of our learning culture. For visitors, you are welcome to read them, contribute to them, and suggest additions. We maintain a monthly pool of $1500 to reward contributors who support our journey of lifelong growth in knowledge and network.

PermalinkLove what we are doing?

Check out our products

Hire us to build your software

Join us, we are also hiring

Visit our Discord Learning Site

Visit our GitHub

PermalinkReferences

https://jesusvalerareales.com/testing-with-test-doubles/

https://ieftimov.com/posts/testing-in-go-test-doubles-by-example/

https://abseil.io/resources/swe-book/html/ch13.html#basic_concepts

Written by

Published on

Dwarves Foundation's Team Blog

Sharing engineering stories and lessons from our team and partner experience.

Sharing engineering stories and lessons from our team and partner experience.