At Dwarves Foundation, we host a few learning sessions to understand some of the technology around us. We regularly pick up topics we find interesting to dive deeper into to understand them better and present our findings. One topic that piqued my interest was the use of message brokers, due to how prevalent their use case is in our projects.

In today's digital world, the exchange of information between different systems and applications is becoming increasingly important. With the rise of cloud computing and the Internet of Things (IoT), there is a growing need for these systems to communicate with each other seamlessly. This is where message brokers come in. A message broker is a middleware solution that provides a platform for exchanging messages between applications, systems, and services. They act as intermediaries, ensuring that messages are delivered reliably and efficiently.

Without message brokers, communication between systems and applications would be much more difficult. They provide a common language that different systems can use to communicate with each other, regardless of the programming language or the hardware used. They also help to ensure that messages are delivered in the correct order, and can handle large volumes of messages without overwhelming the system.

What is a Message Broker?

A Message broker is an intermediary program designed to validate, transform, and route messages. They serve the communication needs between applications.

With a Message broker, the source application (producer) sends a message to a server process that can provide data sorting, routing, message translation, persistence, and delivery to all appropriate destinations (consumers).

There are 2 basic forms of communication with a Message Broker:

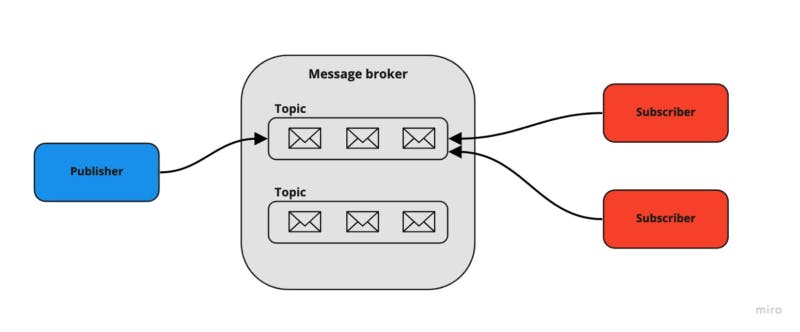

- Publish and Subscribe (Topics)

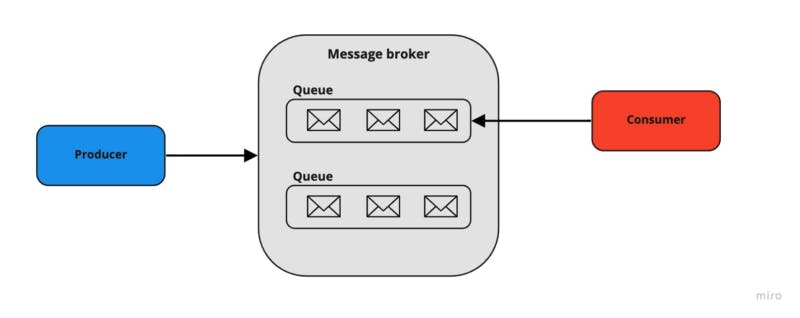

- Point-to-Point (Queues)

When and why to use Message Broker

Message brokers are versatile tools that can address a wide range of business needs across industries and in a variety of enterprise computing environments.

Here are some common ways message brokers are used:

E-commerce order processing and fulfillment: If your business operates online, the reliability of your website and e-commerce platform is crucial to your brand's reputation. Message brokers are an excellent choice for processing online orders because they improve fault tolerance and ensure messages are consumed only once.

Financial transactions and payment processing: It's essential to ensure that payments are sent only once. Using a message broker to handle the data from these transactions ensures that payment information is not lost or accidentally duplicated, provides proof of receipt, and allows systems to communicate reliably even when intermediary networks are unavailable.

Protecting highly sensitive data at rest and in transit: If your industry is heavily regulated or your company faces significant security risks, it's important to choose a messaging solution that supports end-to-end encryption.

Topdev’s online CV creation example

Message Broker helps web servers to send responses to requests quickly instead of being forced to run a resource-consuming procedure on a system. Queuing messages is a good solution when we want to distribute messages to many recipients to reduce the load on processing workers.

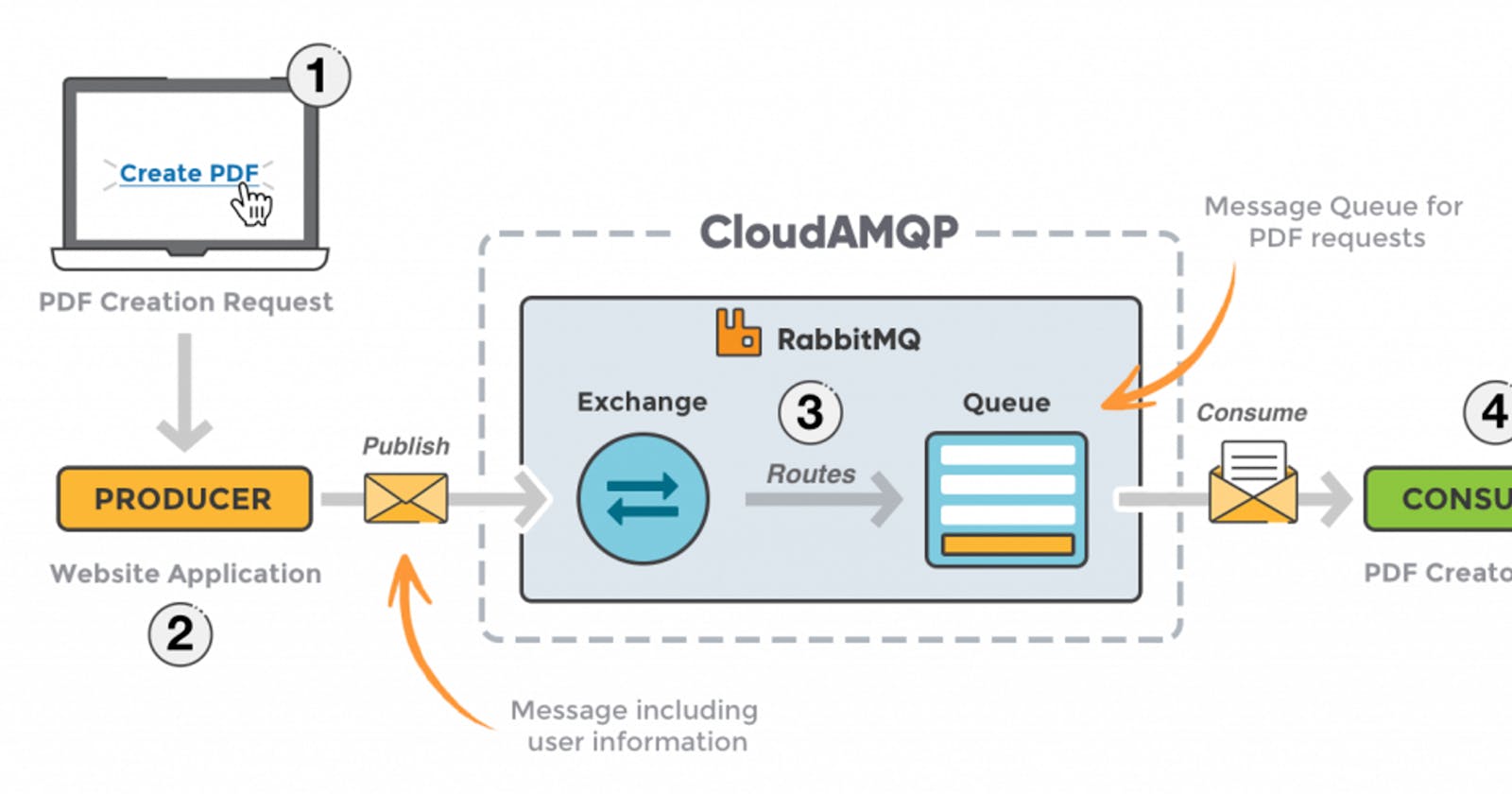

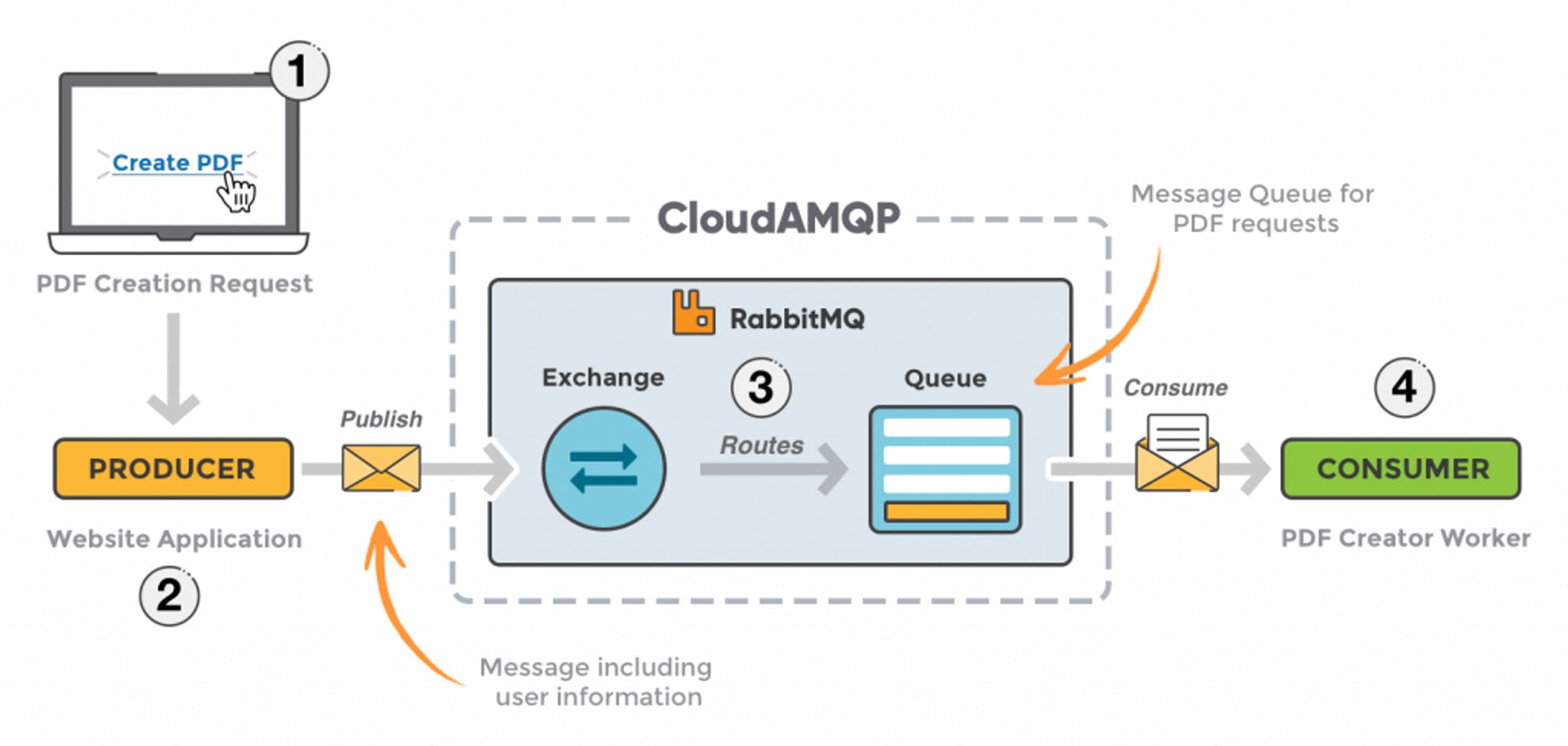

For example, when users are allowed to create PDF files for IT CV templates from TopDev's online CV creation software, the problem is when thousands of users click on the "create PDF" button at the same time, the server receives many requests that will cause some problems such as slow response, overload, and even not being able to create a PDF file due to congestion. In this case, we need to use Message Broker to push these requests into a queue. The mechanism is as follows:

A consumer takes a message from the queue and starts processing the PDF while a producer is adding new messages to the queue. A request can be created in one language and processed in another. The two applications exchange with each other through messages. Therefore, the sending and receiving applications will have low coupling.

User sends a request to create a PDF on the web application.

The web application (producer) sends a message to RabbitMQ containing the requested user data, such as name, email, phone number, etc.

An exchange is agreed upon by the producer application and leads them to the right PDF creation queue.

A PDF creation worker (consumer) receives a task and starts processing the PDF.

Advantages and Disadvantages

There are a few advantages and disadvantages with a job request messaging on message brokers:

Advantages:

Loose coupling: the client can make a request without knowing about the other services. Therefore, it does not need to use a discovery mechanism to find the location of other service instances.

Message buffering: the broker is a buffer for messages until they are processed. This means that both sides do not need to be available at the same time for synchronous message exchange over HTTP (request/response protocol). Instead, the message is queued and is not processed until the consumer is ready. For example, an online store can accept orders even if the ordering service is slow or down because the orders are queued in the message broker and can be processed when the service is available again.

More flexible communication.

Disadvantages:

Potential performance bottleneck: the message broker could be a performance bottleneck. However, modern message brokers are designed for scalability.

Potential single point of failure: the message broker must be continuously accessible. However, modern message brokers are designed for high availability.

Additional operational complexity: the message broker is another component in a system that must be installed, configured, and maintained.

RabbitMQ

RabbitMQ is a message broker that accepts and forwards messages, similar to a post office. When you put mail in a post box, you can be confident that the letter carrier will eventually deliver it to the recipient. RabbitMQ plays the roles of both the post box and post office, as well as the letter carrier.

The main difference between RabbitMQ and the post office is that RabbitMQ doesn't handle physical paper but instead accepts, stores, and forwards binary data called messages.

RabbitMQ and messaging in general use some technical terms:

Producing means sending messages. A program that sends messages is called a publisher(producer).

A producer sends messages to a queue, which is the equivalent of a post box in RabbitMQ. While messages flow through RabbitMQ and the applications, they can only be stored in a queue. A queue is limited by the host's memory and disk capacity and acts as a large message buffer. Many producers can send messages that go to a single queue, and many consumers can try to receive data from a single queue.

Consuming is similar to receiving. A consumer is a program that primarily waits to receive messages.

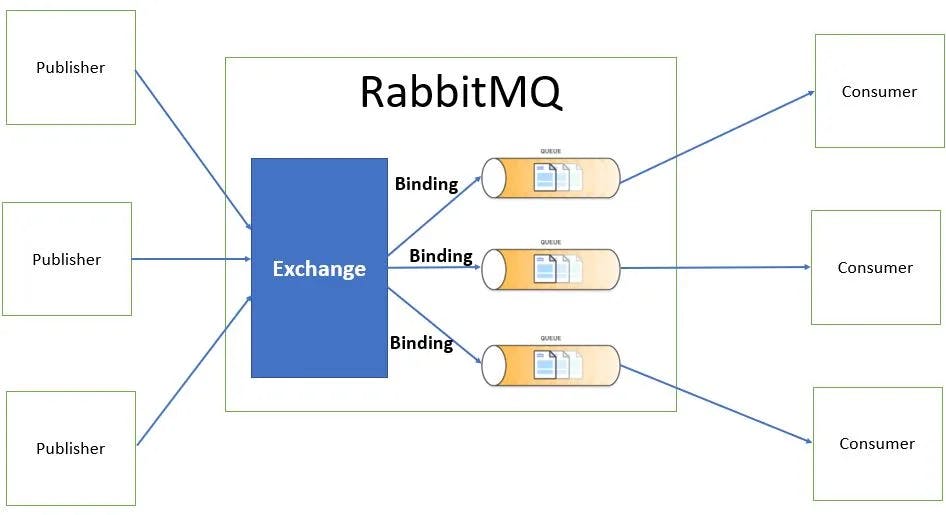

Between the publisher and queue, we also can put a component call exchange which has the main function to decide the message will go to which queues. I will explain more about that late.

Exchanges

The core idea in the messaging model in RabbitMQ is that the producer never sends any messages directly to a queue. In fact, the producer often does not even know if a message will be delivered to any queue at all.

Instead, the producer can only send messages to an exchange. An exchange is a simple component that receives messages from producers on one side, and pushes them to queues on the other side. The exchange must know exactly what to do with a message it receives. Should it be routed to a specific queue or multiple queues, or should it be discarded? The rules for handling messages are defined by the exchange type.

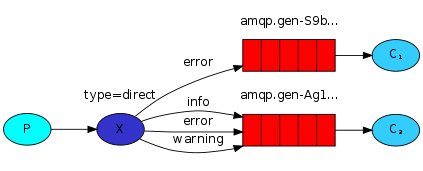

Direct Exchange

The function of Direct exchange is to push messages to the waiting queue based on the routing key. This direct exchange type is quite useful when you want to distinguish messages published to the same exchange by using a simple string identifier.

Fanout Exchange

The function of Fanout exchange is to push messages to all queues attached to it. It is considered as a copy of the message sent to all queues regardless of any routing key. If it is registered, it will be ignored. This exchange is useful when we need to send data to multiple different devices with the same message but different processing at each device, each location.

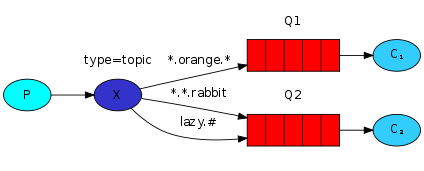

Topic Exchange

Topic exchange will make a wildcard to match the routing key with a routing pattern declared in the binding. Consumers can register about topics they are interested in. The syntax used here is * and #.

Headers Exchange

A header exchange will use the header attributes of the message to route it. Headers Exchange is very similar to Topic Exchange but it routes based on header values instead of routing keys. A message is considered a match if the value of the header matches the value specified when bound.

Common Pattern

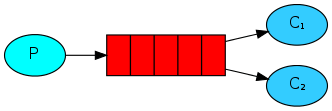

Work Queue - Distributing tasks among workers

The main idea behind Work Queues (aka: Task Queues) is to avoid doing a resource-intensive task immediately and having to wait for it to complete. Instead we schedule the task to be done later. We encapsulate a task as a message and send it to a queue. A worker process running in the background will pop the tasks and eventually execute the job. When you run many workers the tasks will be shared between them.

This concept is especially useful in web applications where it's impossible to handle a complex task during a short HTTP request window.

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

"strings"

"time"

amqp "github.com/rabbitmq/amqp091-go"

)

func failOnError(err error, msg string) {

if err != nil {

log.Panicf("%s: %s", msg, err)

}

}

func main() {

conn, err := amqp.Dial("amqp://guest:guest@localhost:5672/")

failOnError(err, "Failed to connect to RabbitMQ")

defer conn.Close()

ch, err := conn.Channel()

failOnError(err, "Failed to open a channel")

defer ch.Close()

q, err := ch.QueueDeclare(

"task_queue", // name

true, // durable

false, // delete when unused

false, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to declare a queue")

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

body := bodyFrom(os.Args)

err = ch.PublishWithContext(ctx,

"", // exchange

q.Name, // routing key

false, // mandatory

false,

amqp.Publishing {

DeliveryMode: amqp.Persistent,

ContentType: "text/plain",

Body: []byte(body),

})

failOnError(err, "Failed to publish a message")

log.Printf(" [x] Sent %s", body)

}

func bodyFrom(args []string) string {

var s string

if (len(args) < 2) || os.Args[1] == "" {

s = "hello"

} else {

s = strings.Join(args[1:], " ")

}

return s

}

new_task.go is responsible for sending messages to the RabbitMQ message queue. When a message is sent, it is marked with a routing key that indicates its priority. Messages with higher priority will be consumed by workers first. The program uses the amqp library to establish a connection to the RabbitMQ server, create a channel, declare a queue and publish messages to it.

package main

import (

"bytes"

"log"

"time"

amqp "github.com/rabbitmq/amqp091-go"

)

func failOnError(err error, msg string) {

if err != nil {

log.Panicf("%s: %s", msg, err)

}

}

func main() {

conn, err := amqp.Dial("amqp://guest:guest@localhost:5672/")

failOnError(err, "Failed to connect to RabbitMQ")

defer conn.Close()

ch, err := conn.Channel()

failOnError(err, "Failed to open a channel")

defer ch.Close()

q, err := ch.QueueDeclare(

"task_queue", // name

true, // durable

false, // delete when unused

false, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to declare a queue")

err = ch.Qos(

1,// prefetch count0,// prefetch sizefalse,// global

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to set QoS"

msgs, err := ch.Consume(

q.Name, // queue

"", // consumer

false, // auto-ack

false, // exclusive

false, // no-local

false, // no-wait

nil, // args

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to register a consumer")

var forever chan struct{}

go func() {

for d := range msgs {

log.Printf("Received a message: %s", d.Body)

dotCount := bytes.Count(d.Body, []byte("."))

t := time.Duration(dotCount)

time.Sleep(t * time.Second)

log.Printf("Done")

d.Ack(false)

}

}()

log.Printf(" [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C")

<-forever

}

worker.go, on the other hand, is responsible for consuming messages from the queue and processing them. When a worker starts, it declares a queue and binds it to the exchange, specifying the routing key that it wants to consume. The worker then waits for messages from the queue and processes them one by one. In this tutorial, the processing time is simulated using the time.Sleep() function.

In the above example, we declare a queue with function:

q, err := ch.QueueDeclare(

"hello", // name

true, // durable

false, // delete when unused

false, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

Function have params:

name: The name of the queue to declare. It's a mandatory parameter and must be a string.durable: A boolean value that indicates if the queue should survive a broker restart or not. Ifdurableis set totrue, the queue will survive a broker restart, and if it's set tofalse, the queue will not.delete when unused: A boolean value that indicates if the queue should be deleted when it's no longer in use. If this is set totrue, the queue will be deleted automatically when there are no more consumers subscribed to it.exclusive: A boolean value that indicates if the queue should be exclusive to the current connection. If this is set totrue, only the current connection can access the queue. If set tofalse, other connections can also access the queue.no-wait: A boolean value that indicates if the queue should be declared as a passive queue or not. If this is set totrue, the broker will not wait for a response from the server before sending the next command.arguments: A table of additional arguments to pass when declaring the queue. These arguments are optional and can be used to specify various queue properties such as message TTL (time-to-live), maximum length, and more.

The function returns the following values:

q: The name of the queue that was declared by the broker. If thenameparameter was empty, the broker will generate a unique name for the queue.err: An error value if there was an error declaring the queue. If the queue was declared successfully,errwill benil.

Publish/Subscribe - Sending messages to many consumers at once

To create Publish/Subscribe we need to:

create a fanout exchange and a queue

create relationship between exchange and a queue is called a binding

The producer program that emits log messages doesn't differ much from the previous part. The most significant change is that we now want to publish messages to our logs exchange instead of the nameless one. We need to supply a routingKey when sending, but its value is ignored for fanout exchanges. Here's the code for the emit_log.go script:

emit_log.go

package main

import (

"context"

"log"

"os"

"strings"

"time"

amqp "github.com/rabbitmq/amqp091-go"

)

func failOnError(err error, msg string) {

if err != nil {

log.Panicf("%s: %s", msg, err)

}

}

func main() {

conn, err := amqp.Dial("amqp://guest:guest@localhost:5672/")

failOnError(err, "Failed to connect to RabbitMQ")

defer conn.Close()

ch, err := conn.Channel()

failOnError(err, "Failed to open a channel")

defer ch.Close()

err = ch.ExchangeDeclare(

"logs", // name

"fanout", // type

true, // durable

false, // auto-deleted

false, // internal

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to declare an exchange")

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 5*time.Second)

defer cancel()

body := bodyFrom(os.Args)

err = ch.PublishWithContext(ctx,

"logs", // exchange

"", // routing key

false, // mandatory

false, // immediate

amqp.Publishing{

ContentType: "text/plain",

Body: []byte(body),

})

failOnError(err, "Failed to publish a message")

log.Printf(" [x] Sent %s", body)

}

func bodyFrom(args []string) string {

var s string

if (len(args) < 2) || os.Args[1] == "" {

s = "hello"

} else {

s = strings.Join(args[1:], " ")

}

return s

}

receive_log.go

package main

import (

"log"

amqp "github.com/rabbitmq/amqp091-go"

)

func failOnError(err error, msg string) {

if err != nil {

log.Panicf("%s: %s", msg, err)

}

}

func main() {

conn, err := amqp.Dial("amqp://guest:guest@localhost:5672/")

failOnError(err, "Failed to connect to RabbitMQ")

defer conn.Close()

ch, err := conn.Channel()

failOnError(err, "Failed to open a channel")

defer ch.Close()

err = ch.ExchangeDeclare(

"logs", // name

"fanout", // type

true, // durable

false, // auto-deleted

false, // internal

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to declare an exchange")

q, err := ch.QueueDeclare(

"", // name

false, // durable

false, // delete when unused

true, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to declare a queue")

err = ch.QueueBind(

q.Name, // queue name

"", // routing key

"logs", // exchange

false,

nil,

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to bind a queue")

msgs, err := ch.Consume(

q.Name, // queue

"", // consumer

true, // auto-ack

false, // exclusive

false, // no-local

false, // no-wait

nil, // args

)

failOnError(err, "Failed to register a consumer")

var forever chan struct{}

go func() {

for d := range msgs {

log.Printf(" [x] %s", d.Body)

}

}()

log.Printf(" [*] Waiting for logs. To exit press CTRL+C")

<-forever

}

To declare an exchange, we use the function:

err = ch.ExchangeDeclare(

"logs", // name

"fanout", // type

true, // durable

false, // auto-deleted

false, // internal

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

name: The name of the exchange to declare. This is a mandatory parameter and must be a string.type: The type of the exchange to declare. There are four types of exchanges in RabbitMQ:fanout,direct,topic, andheaders. In this case, we're using afanoutexchange, which will broadcast all messages to all bound queues.durable: A boolean value that indicates if the exchange should survive a broker restart or not. Ifdurableis set totrue, the exchange will survive a broker restart, and if it's set tofalse, the exchange will not.auto-deleted: A boolean value that indicates if the exchange should be deleted when it's no longer in use. If this is set totrue, the exchange will be deleted automatically when there are no more queues bound to it.internal: A boolean value that indicates if the exchange should be marked as internal. If this is set totrue, the exchange will not be directly accessible to clients, and it can only be used for internal purposes.no-wait: A boolean value that indicates if the exchange should be declared as passive or not. If this is set totrue, the broker will not wait for a response from the server before sending the next command.arguments: A table of additional arguments to pass when declaring the exchange. These arguments are optional and can be used to specify various exchange properties such as message TTL (time-to-live), alternate exchange, and more.

The function returns an error value if there was an error declaring the exchange. If the declaration was successful, the error value will be nil.

After that, we need to binding queue and exchange to allow queue receive message from the exchange. To binding we use the function:

err = ch.QueueBind(

q.Name, // queue name

"", // routing key

"logs", // exchange

false,

nil,

)

queue name: The name of the queue to which the binding should be applied. This is a mandatory parameter and must be a string.routing key: The routing key to use for the binding. If it's an empty string (""), the binding will receive all messages from the exchange. If it's a non-empty string, the binding will only receive messages with matching routing keys.exchange: The name of the exchange to which the queue should be bound. This is a mandatory parameter and must be a string.no-wait: A boolean value that indicates if the binding should be done asynchronously or not. If it's set totrue, the broker will not wait for a response from the server before sending the next command.arguments: A table of additional arguments to pass when binding the queue. These arguments are optional and can be used to specify various binding properties such as headers, message TTL (time-to-live), and more.

The function returns an error value if there was an error binding the queue. If the binding was successful, the error value will be nil.

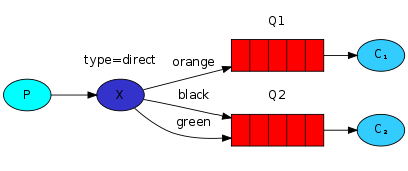

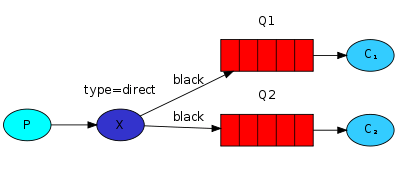

Routing - Receiving messages selectively

If with publish/subcribe we allow all queue which bind with the exchange can receive the message. In the routing, our target is limit the right to receive message by route's name. It means only the queue binding with the exchange by a specific name is allowed to receive the message.

For example, in the above picture, the Q2 is only received message with the key route black and green, while the Q1 is received message with route's key orange. In addition, it is perfectly legal to bind multiple queues with the same binding key.

About the exchange, instead of fanout we'll send messages to a direct exchange. And when public the message we also to provide with a list of route's name which we want to send the message through.

Topic - Receiving messages based on a pattern

Messages sent to a topic exchange can't have an arbitrary routing_key - it must be a list of words, delimited by dots. The words can be anything, but usually they specify some features connected to the message. A few valid routing key examples: "stock.usd.nyse", "nyse.vmw", "quick.orange.rabbit". There can be as many words in the routing key as you like, up to the limit of 255 bytes.

The binding key must also be in the same form. The logic behind the topic exchange is similar to a direct one - a message sent with a particular routing key will be delivered to all the queues that are bound with a matching binding key. However there are two important special cases for binding keys:

\* (star) can substitute for exactly one word.

\# (hash) can substitute for zero or more words.

It's easiest to explain this in an example:

Delayed message

Delaying a message means setting a time for the message to be sent that is not immediate. For example, we may want to send a message one minute after it is made public.

By combining Time-To-Live (TTL) and Dead Letter Exchange, we can publish a message to a queue that will expire its message after the TTL and then reroute it to the exchange with the dead-letter routing key so that it ends up in a queue.

Here are the step-by-step instructions:

Declare the pending queue.

Set the x-dead-letter-exchange argument property to the default value, "".

Set the argument property x-dead-letter-routing-key to the name of the destination queue.

Set the x-message-ttl argument property to the number of milliseconds you want the message to be delayed.

package main

import (

"log"

"github.com/streadway/amqp"

)

func main() {

// Connect to RabbitMQ server

conn, err := amqp.Dial("amqp://nprabbitmq:d8qSFi9pdsFQ53tH@localhost:5682/")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to connect to RabbitMQ server: %v", err)

}

defer conn.Close()

// Create a channel

ch, err := conn.Channel()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to open a channel: %v", err)

}

defer ch.Close()

// Set the x-dead-letter-exchange argument property to the default value “”.

args := make(amqp.Table)

args["x-dead-letter-exchange"] = ""

// Set the argument property x-dead-letter-routing-key to the name of the destination queue.

args["x-dead-letter-routing-key"] = "destination_queue"

// Set the x-message-ttl argument property to the number of milliseconds you want the message to be delayed.

args["x-message-ttl"] = 6000 // 1 minute

// Declare the pending queue

q, err := ch.QueueDeclare(

"pending_queue", // name

false, // durable

false, // delete when unused

false, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

args, // arguments

)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to declare a queue: %v", err)

}

// Declare the destination queue

_, err = ch.QueueDeclare(

"destination_queue", // name

true, // durable

false, // delete when unused

false, // exclusive

false, // no-wait

nil, // arguments

)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to declare a queue: %v", err)

}

// Publish a message to the pending queue

body := "Hello, World!"

err = ch.Publish(

"", // exchange

q.Name, // routing key

false, // mandatory

false, // immediate

amqp.Publishing{

ContentType: "text/plain",

Body: []byte(body),

},

)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed to publish a message: %v", err)

}

log.Println("Message published successfully!")

}

The x-dead-letter-exchange and x-dead-letter-routing-key arguments are used to define where messages should be routed after they have expired in a RabbitMQ queue.

When a message's time-to-live (TTL) expires in a queue, it becomes a "dead letter". The x-dead-letter-exchange argument specifies the name of the exchange where dead-lettered messages should be sent. The x-dead-letter-routing-key argument specifies the routing key that should be used to route these messages to the desired queue.

In the code snippet provided, the x-dead-letter-exchange argument is set to an empty string, which means that dead-lettered messages will be routed to the default exchange. The x-dead-letter-routing-key argument is set to "destination_queue", which means that dead-lettered messages will be routed to the "destination_queue".

By using these arguments, the program ensures that any messages that expire in the "pending_queue" will be automatically sent to the "destination_queue". This can be useful in cases where a delay is needed before processing a message, or when retrying failed messages.

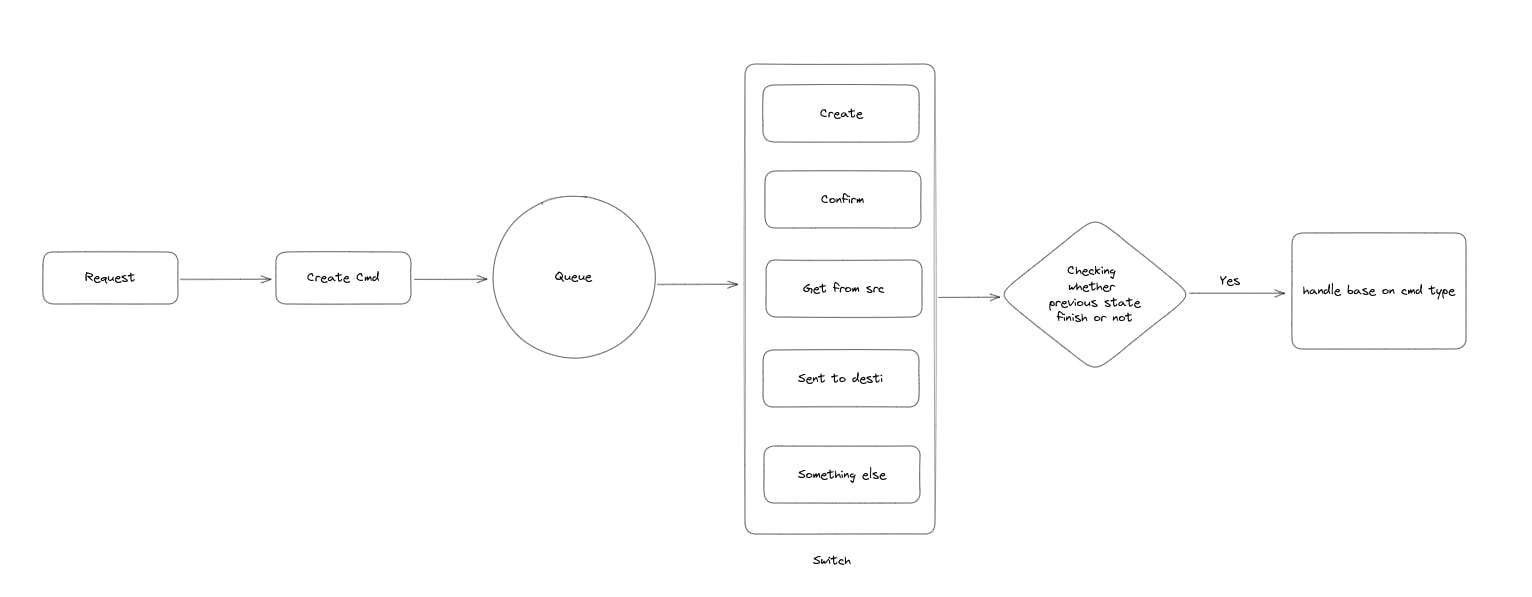

Handle the process with many steps with rabbitMQ

Problem: We have a banking system. It has many steps that need to handle in order (creating, confirming, get money from the source, sent it to the destination).

The solution for it is to create the message with a command type. This type will use to determine the process in the future. In addition, to make sure the process handle in order, we have to create a function to check the state of the transaction is invalid or not. Then, we just need to handle the process base on the command type.

Compare RabbitMQ and Kafka

| Parameter | RabbitMQ | Kafka |

| Performance | Up to 10K messages per second | Up to 1 million messages per second |

| Data Type | Transactional | Operational |

| Synchronicity of messages | Can be synchronous/asynchronous | Durable message store that can replay messages |

| Topology | Exchange type: Direct, Fan out, Topic, Header-based | Publish/subscribe based |

| Payload Size | No constraints | Default 1MB limit |

| Usage Cases | Simple use cases | Massive data/high throughput cases |

| Data Flow | Distinct bounded data packets in the form of messages | Unbounded continuous data in the form of key-value pairs. |

| Data Unit | Message | Continuous stream |

| Data Tracking | Broker/Publisher keeps track of message status (read/unread) | Broker/Publisher keeps only unread messages; it doesn’t retain sent messages. |

| Broker/Publisher Type | Smart | Dumb |

| Consumer Type | Dumb | Smart |

| Routing messages | Complex routing is possible based on event types | Complex routing is not possible; however, we can subscribe to individual topics. |

| Topology | Exchange queue topology | publish/subscribe topology |

| Message delivery system | Message pushed to specific queues | Pull-based model; consumer pulls messages as required |

| Message management | Prioritize messages | Order/Retain/Guarantee messages |

| Message Retention | Acknowledgment based | Policy-based (e.g., ten days) |

| Event storage structure | Queue | Logs |

| Consumer Queues | Decoupled Consumer queues | Coupled consumer partition/groups |

Conclusion

This article provides a comprehensive overview of message brokers and their importance in today's software applications. It defines message brokers, their basic forms of communication, and when and why to use them. It then introduces RabbitMQ, a popular message broker, and explains some common patterns used with it, such as work queues and publish/subscribe. The article also covers some basic terms related to message brokers, such as exchanges, queues, routing keys, and bindings, and explains how they work together to facilitate message communication between different applications. Finally, the article compares RabbitMQ and Kafka, another popular message broker, in terms of performance, data type, synchronicity of messages, topology, payload size, usage cases, data flow, data unit, data tracking, broker/publisher type, consumer type, routing messages, topology, message delivery system, message management, message retention, event storage structure, and consumer queues.

Contributing

At Dwarves, we encourage our people to read, write, share what we learn with others, and contributing to the Brainery is an important part of our learning culture. For visitors, you are welcome to read them, contribute to them, and suggest additions. We maintain a monthly pool of $1500 to reward contributors who support our journey of lifelong growth in knowledge and network.

Love what we are doing?

Check out our products

Hire us to build your software

Join us, we are also hiring

Visit our Discord Learning Site

Visit our GitHub