Photo by Stackie Jia on Unsplash

Approaches to manage concurrent workloads, like worker pools and pipelines

Introduction

Go provides us great and convenient ways to write concurrent programs with high performance to execute tasks concurrently (perhaps in parallel if the program is run on a machine with multiple physical cores, GOMAXPROCS are automatically set to the number of physical cores of the machine that the program is running on)

While the Go concurrency primitives are easy to work with (it means it's easy to create the Go concurrency primitives and start using them), but they don't prevent us the developers to write something incorrectly or buggy. They should be used with great care and ideally they should be combined together to achieve some concurrency patterns to be fit in different use cases or contexts where we might solve/handle our problems/business concurrently.

Concurrency patterns in Go are different ways to put Go’s concurrency primitives together to build interesting structures and get our code to respond well to a lot of things happening at once. Below are four popular concurrency patterns in Go that helps handle large amount of workloads concurrently in a safe and elegant way.

This post will explain these patterns with a simple example and walk you through the code as well as the decision-making when writing these codes.

The Patterns

The Workers Pool pattern

The first popular one should be the workers pool pattern. Goroutine pools are a way of limiting the number of goroutines that can run concurrently. This pattern involves creating a fixed number of goroutines at startup and then using a channel to queue up work. When a new task arrives, it is added to the channel, and one of the idle goroutines picks it up and executes it.

// worker simply double the number received from the jobs channel and send it to the results channel

func worker(id int, wg *sync.WaitGroup, jobs <-chan int, results chan<- int) {

defer wg.Done()

for j := range jobs {

fmt.Println("worker", id, "processing job", j)

results <- j * 2

}

}

func main() {

const (

numJobs, numWorkers = 5, 3

)

var (

jobs = make(chan int, numJobs)

results = make(chan int, numJobs)

workerWg = new(sync.WaitGroup)

)

workerWg.Add(numWorkers)

// Create a pool of 3 workers

for w := 1; w <= numWorkers; w++ {

go worker(w, workerWg, jobs, results)

}

go func() {

defer close(results)

workerWg.Wait()

}()

// Add jobs to the queue

go func() {

defer close(jobs)

for j := 1; j <= numJobs; j++ {

jobs <- j

}

}()

// Collect results from the workers

for res := range results {

fmt.Println("RESULT:", res)

}

}

The disadvantages of this pattern

Limited scalability

The worker pool pattern, with a fixed number of workers, can be limited in terms of scalability. If the workload increases beyond the capacity of the worker pool, performance may suffer. One solution to this problem is to use a dynamic worker pool. In a dynamic worker pool, the number of workers varies based on the workload. When there are more tasks to be processed, the pool increases the number of workers, and when the workload decreases, it reduces the number of workers.

To implement a dynamic worker pool, we can use a combination of channels and goroutines. We can create a channel to receive tasks and another channel to send results. We can also create a goroutine that listens to the task channel and assigns tasks to available workers. Each worker is a goroutine that receives a task from the worker channel, processes it, and sends the result back to the result channel. To dynamically adjust the number of workers, we can use a separate goroutine that monitors the workload and adjusts the number of workers accordingly. By using a dynamic worker pool, we can achieve better scalability and utilization of resources. However, it requires careful tuning of parameters such as the workload threshold and the rate of worker creation/destruction to avoid overloading the system or creating too many unnecessary goroutines.

Resource management

Managing resources such as memory and CPU usage can be challenging with the worker pool pattern. Since the number of workers is fixed, it can be difficult to optimize resource usage for different types of workloads. If a worker takes too long to complete a task, we can use a timeout mechanism for tasks, such that the task can be timed out and reassigned to another worker. This ensures that no worker is blocked for an extended period of time and helps maintain the overall performance of the system.

Task prioritization

The worker pool pattern does not provide a built-in mechanism for task prioritization. This means that all tasks are treated equally, regardless of their importance or urgency. We can introduce a priority queue data structure to the workers pool pattern. A priority queue is a data structure that stores elements with associated priorities and allows for efficient retrieval of the element with the highest priority.

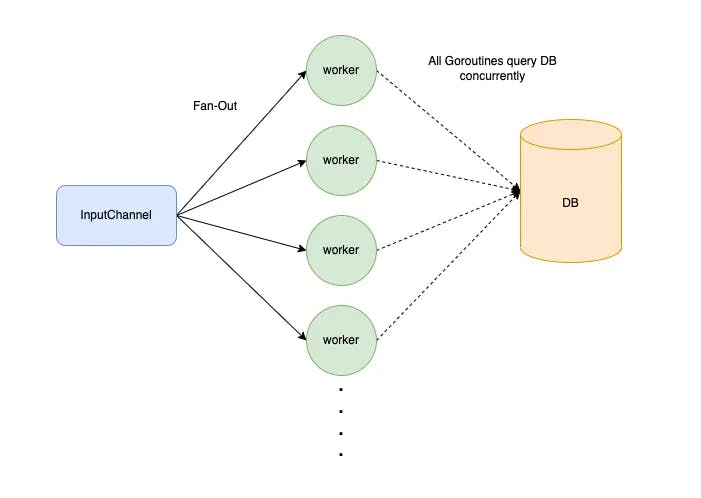

The Fan-Out/Fan-In pattern

Fan-out/fan-in is a pattern for parallelizing work across multiple goroutines. The idea is to split the work into smaller chunks and distribute them across a pool of workers. Once all the workers have finished processing their chunks, the results are collected and combined.

Let’s imagine you have a large stream of input data that need to be processed (validate, enrich, transform, etc) and obviously you will not want to do that sequentially then the fan-out/fan-in pattern comes in to help us do this concurrently.

The fan-out part of the pattern involves distributing work among multiple worker goroutines. These goroutines work concurrently, each handling a portion of the tasks. This approach helps to increase throughput and process large datasets more efficiently. The fan-in aspect of the pattern involves collecting the results from the worker goroutines and combining them into a single output. This process is typically done using a dedicated goroutine that listens to the individual output channels of the workers, merges the results, and sends them to a single output channel.

The fan-out, fan-in pattern is particularly useful in situations where tasks can be divided into smaller, independent units and processed concurrently. This pattern not only improves application performance but also enhances code maintainability and readability by separating the concerns of distributing tasks and aggregating results.

// simulateDownload simulates downloading a file and returns its content.

func simulateDownload(url string) string {

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(100)) * time.Millisecond)

return fmt.Sprintf("Content of %s", url)

}

// downloader downloads a list of URLs and returns the content.

func downloader(urls []string) <-chan string {

out := make(chan string)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for _, url := range urls {

out <- simulateDownload(url)

}

}()

return out

}

// worker processes the content and returns the number of words.

func worker(in <-chan string) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for content := range in {

fmt.Println(time.Now().Format("2006-01-02 15:04:05.000000000 -0700 MST"))

fmt.Printf("Processing content: %s\\n", content)

words := strings.Fields(content)

out <- len(words)

}

}()

return out

}

// merger merges the results from multiple workers.

func merger(ins ...<-chan int) <-chan int {

out := make(chan int)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(len(ins))

for _, in := range ins {

go func(in <-chan int) {

defer wg.Done()

for n := range in {

fmt.Printf("Merging result: %d\\n\\n", n)

out <- n

}

}(in)

}

go func() {

defer close(out)

wg.Wait()

}()

return out

}

func main() {

rand.Seed(time.Now().UnixNano())

urls := []string{

"<https://example.com/file1.txt>",

"<https://example.com/file2.txt>",

"<https://example.com/file3.txt>",

"<https://example.com/file4.txt>",

"<https://example.com/file5.txt>",

}

downloadStream := downloader(urls)

numWorkers := 3

workerChannels := make([]<-chan int, numWorkers)

for i := 0; i < numWorkers; i++ {

workerChannels[i] = worker(downloadStream)

}

merged := merger(workerChannels...)

totalWordCount := 0

for count := range merged {

totalWordCount += count

}

fmt.Printf("Total word count: %d\\n", totalWordCount)

}

Here’s a breakdown of the code:

Import necessary packages.

Define

simulateDownload(url string)function, which simulates downloading a file from the provided URL and returns its content as a string.Define

downloader(urls []string)function, which takes a slice of URLs and returns a channel that sends the content of each URL. It launches a goroutine that iterates over the URLs, simulates the download, and sends the content through the channel. The channel is closed after all URLs have been processed. It will be fan-out part*: the*downloaderfunction creates a singledownloadStreamchannel that sends the content of each downloaded file. Later, we will create multiple worker goroutines that listen to this shared channel, effectively fanning out the work to be done concurrently.Define

worker(in <-chan string)function, which takes a channel of strings as input and returns a channel of integers. It launches a goroutine that reads the content from the input channel, prints the processing timestamp and content, counts the number of words in the content, and sends the count through the output channel. The output channel is closed after all content has been processed.Define

merger(ins ...<-chan int)function, which takes a variadic parameter of channels with integer values and returns a channel with integer values. It merges the input channels into a single output channel. Async.WaitGroupis used to wait for all input channels to be processed, after which the output channel is closed. It will be fan-in part*: the*mergerfunction combines the results from multiple worker goroutines by listening to their individual output channels. It uses async.WaitGroupto ensure that it waits for all the worker goroutines to complete before closing its output channel.In the

mainfunction, seed the random generator, define a slice of URLs, and create a download stream by calling thedownloader()function.Define the number of workers, create a slice of worker channels, and start the worker goroutines with the download stream as input.

Merge the worker channels using the

merger()function.Iterate over the merged channel to compute the total word count.

Print the total word count.

The disadvantages of this pattern

Increased complexity

The fan-out/fan-in pattern can add complexity to your code, especially if you need to handle errors or timeouts. It can also make it harder to reason about the behavior of your program. To handle errors or timeouts, you can use the context cancellation, or use the context package to propagate cancellation signals to all the goroutines involved in the fan-out/fan-in pattern. This can help ensure that resources are released promptly and that your program doesn't hang indefinitely.

Resource consumption

Creating too many goroutines can lead to excessive resource consumption, which can cause performance issues or even crashes. This is particularly true if the sub-tasks are short-lived and the overhead of creating and managing goroutines outweighs the benefits. To avoid excessive resource consumption, you can limit the number of goroutines that are created at any given time. One way to do this is to use a worker pool, where a fixed number of goroutines are created upfront and then used to process tasks as they become available.

Synchronization overhead

Coordinating the results of multiple goroutines can introduce synchronization overhead, which can slow down your program and increase the likelihood of race conditions or deadlocks. If possible, try to design your program so that synchronization is only necessary when aggregating the results of the sub-tasks to avoid unnecessary synchronization. For example, you can use channels to pass data between goroutines instead of shared memory, which can reduce the likelihood of race conditions or deadlocks.

The Pipeline pattern

A pipeline is a series of stages that takes in data, processes them, and passes them to another stage. Here’s an example of a simple pipeline without using Goroutine:

func main() {

input := 1

// Example 1:

multiply(add(input, 1), 2)

// Example 2:

// We can rearrange the stages to get diff result

add(multiply(input, 2), 1)

}

func add(x int, y int) int {

return x + y

}

func multiply(x int, y int) int {

return x * y

}

The benefit of a pipeline is evident:

It separates the concerns of each stage in the pipeline. Each stage is responsible for one and only one thing.

The stages are modular and allow us to mix and match how stages are combined.

The stages in the example above run sequentially. Each can only begin after the previous stage has processed all the data. Leveraging the Goroutine and channel, stages can run and process data concurrently. First, we transform our add and multiplyfunction to take in an inputCh and outputs a resultCh.

func generator(doneCh chan struct{}, input []int) chan int {

inputCh := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(inputCh)

for _, data := range input {

select {

case <-doneCh:

return

case inputCh <- data:

}

}

}()

return inputCh

}

func add(doneCh chan struct{}, inputCh chan int) chan int {

addRes := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(addRes)

for data := range inputCh {

result := data + 1

select {

case <-doneCh:

return

case addRes <- result:

}

}

}()

return addRes

}

func multiply(doneCh chan struct{}, inputCh chan int) chan int {

multiplyRes := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(multiplyRes)

for data := range inputCh {

result := data * 2

select {

case <-doneCh:

return

case multiplyRes <- result:

}

}

}()

return multiplyRes

}

func main() {

input := []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

doneCh := make(chan struct{})

defer close(doneCh)

inputCh := generator(doneCh, input)

resultCh := multiply(doneCh, add(doneCh, inputCh))

for res := range resultCh {

fmt.Println(res)

}

}

Here’s a breakdown of the code:

We create a data stream using the

generatorfunctionWe create a

doneChand pass to all Goroutines for explicit cancellationWe then chain the

addandmultiplystage togetherWhenever the

addfunction has done processing an input. It will immediately pass the result to the multiply stage for further processing

Each stage processes the data concurrently and immediately passes it to the next stage once it’s done. Moreover, the multiply and the add stage can be mixed and matched to produce different results.

The disadvantages of this pattern

Increased complexity

The pipeline pattern can become complex when dealing with multiple stages and channels. This complexity can make it difficult to debug and maintain the code. To reduce the complexity of the pipeline pattern, it is important to keep each stage simple and focused on a specific task. This will make it easier to debug and maintain the code.

Blocking

If one stage of the pipeline is blocked, it can cause the entire pipeline to block. This can lead to performance issues and slow down the processing of data. To avoid blocking in the pipeline, non-blocking channels can be used. This will allow the pipeline to continue processing data even if one stage is blocked.

Data Loss

If the pipeline is not designed properly, it can result in data loss. For example, if a channel is not buffered and a stage is not ready to receive data, the data will be lost. To prevent data loss, buffered channels can be used. This will ensure that data is not lost if a stage is not ready to receive data.

Proper error handling should be implemented in each stage of the pipeline to handle any errors that may occur. This will help to prevent the pipeline from crashing and losing data.

The Semaphore pattern

As you spawn more Goroutines to process requests concurrently, this leaves us with another problem. What happens if all your Goroutines access the same shared resources, say a remote cache? Bombarding your cache with an unbounded number of concurrent requests is a surefire recipe to bring down your cache immediately. This is where the Semaphore comes in handy.

Unlike mutex lock, which allows a single thread to access a resource at a time, Semaphore allows N threads to access a resource at a time. Using the concept of a buffered channel, we can design a semaphore easily.

type Semaphore struct {

semaCh chan struct{}

}

func NewSemaphore(maxReq int) *Semaphore {

return &Semaphore{

semaCh: make(chan struct{}, maxReq),

}

}

func (s *Semaphore) Acquire() {

s.semaCh <- struct{}{}

}

func (s *Semaphore) Release() {

<-s.semaCh

}

The

NewSemaphoreinitiates aSemaphoreby creating a buffered channel with the capacity ofmaxReqWhen a Goroutine

Acquirea semaphore, we send an empty struct tosemaChWhen the buffered channel is full, call to

Acquirewill be blockedWhen a Goroutine

Releasea semaphore, an empty struct will be sent out of the channel, creating space in the buffered channel for subsequentAcquire

Let’s take a look at an example:

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

semaphore := NewSemaphore(2)

for idx := 0; idx < 10; idx++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(taskID int) {

semaphore.Acquire()

defer wg.Done()

defer semaphore.Release()

msg := fmt.Sprintf(

"%s Running worker %d",

time.Now().Format("15:04:05"),

taskID,

)

fmt.Println(msg)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}(idx)

}

wg.Wait()

}

We create a semaphore with the capacity of

2We spawn ten Goroutines to process certain task

Each Goroutine acquires a semaphore before processing

Since there are ten tasks and the maximum number of concurrent tasks is

2, the total time needed to process all tasks will be five seconds (Each task takes one second)

The disadvantages of this pattern

Deadlocks

One of the main disadvantages of the Semaphore pattern is the potential for deadlocks. Deadlocks occur when two or more processes are waiting for each other to release a resource, resulting in a deadlock situation where none of the processes can proceed. To avoid deadlocks, it is important to ensure that all resources are released after they have been used. In Golang, this can be achieved by using the deferstatement to ensure that resources are always released, even if an error occurs.

Starvation

Another disadvantage of the Semaphore pattern is the potential for starvation. Starvation occurs when a process is unable to access a shared resource because other processes are constantly accessing it.

To avoid starvation, it is important to implement a fair scheduling algorithm that ensures that all processes have equal access to the shared resource. In Golang, this can be achieved by using a sync.Mutex to lock the shared resource and a sync.Cond to signal when the resource is available.

Performance Overhead

The Semaphore pattern can also introduce performance overhead due to the additional synchronization mechanisms required to control access to the shared resource. To minimize performance overhead, it is important to use the Semaphore pattern only when necessary and to carefully consider the number of resources that need to be shared. In Golang, this can be achieved by using buffered channels to limit the number of goroutines that can access the shared resource at any given time.

Considering the number of goroutines

Goroutines are considered to be lightweight because they use little memory and resources plus their initial stack size is small. Prior to version 1.2 the stack size started at 4K and now as of version 1.4 it starts at 8K. The stack has the ability to grow as needed.

The operating system schedules threads to run against available processors and the Go runtime schedules goroutines to run within a logical processor that is bound to a single operating system thread. By default, the Go runtime allocates a single logical processor to execute all the goroutines that are created for our program. Even with this single logical processor and operating system thread, hundreds of thousands of goroutines can be scheduled to run concurrently with amazing efficiency and performance. It is not recommended to add more that one logical processor, but if you want to run goroutines in parallel, Go provides the ability to add more via the GOMAXPROCS environment variable or runtime function.

There are some problems and key notes to consider when running a huge number of goroutines with GOMAXPROCS(1) a.k.a running them on a single thread or logical processor:

Performance Issues: Running a large number of goroutines on a single processor can cause performance issues due to the overhead of context switching between them. This can lead to slower execution times and increased memory usage.

The typical file descriptor limits of machines nowadays vary depending on the operating system and its configuration. Here are some examples:

Linux: The default limit is often set to 1024, but it can be increased by modifying the

/etc/security/limits.conffile or using theulimitcommand. Some distributions may have higher default limits.macOS: The default limit is often set to 256, but it can be increased by modifying the

/etc/sysctl.conffile or using theulimitcommand.Windows: The default limit is often set to a very high value (e.g. 16 million), but it can be increased or decreased using the

SetProcessHandleCountfunction.

It's important to note that increasing the file descriptor limit can have performance implications, as each open file consumes system resources. Therefore, it's generally recommended to only increase the limit if your application requires it and to monitor resource usage carefully.

Deadlocks and Race Conditions: When multiple goroutines access shared resources concurrently, it can lead to deadlocks and race conditions. These issues can be difficult to debug and fix, especially when dealing with a large number of goroutines.

Resource Limitations: Running a large number of goroutines can also lead to resource limitations, such as running out of memory or hitting file descriptor limits. It's important to monitor resource usage and adjust the number of goroutines accordingly.

When multiple goroutines are running on a single thread (logical processor), the operating system has to perform context switching between them. Context switching is the process of saving the current state of a running process or thread and restoring the saved state of another process or thread so that it can continue execution from where it left off.

The overhead of context switching between goroutines depends on several factors, including the number of goroutines running on the thread, the frequency of context switches, and the complexity of the tasks being performed by the goroutines.

If there are many goroutines running on a single thread, the frequency of context switches will be high, which can lead to increased overhead. This is because each time a context switch occurs, the operating system has to save the state of the currently running goroutine and restore the state of the next goroutine to be executed. This involves copying data between memory locations, which can be time-consuming.

In addition, if the tasks being performed by the goroutines are complex and require a lot of CPU time, the overhead of context switching can be even higher. This is because each time a context switch occurs, the CPU has to spend time re-loading its caches with the data needed by the new goroutine, which can take longer if the data is not already in the cache.

To minimize the overhead of context switching between goroutines, it is important to carefully manage the number of goroutines running on a single thread and to ensure that they are performing tasks that are well-suited to concurrent execution. This can involve using techniques such as load balancing and task prioritization to ensure that the most important tasks are executed first and that the workload is evenly distributed across all available threads.

Design Considerations: When designing an application that uses a large number of goroutines, it's important to consider the overall architecture and ensure that it is scalable and maintainable. This may involve breaking up tasks into smaller, more manageable pieces or using a distributed system architecture.

Use channels for communication: Goroutines communicate with each other using channels. Using channels instead of shared memory avoids race conditions and makes it easier to reason about your code.

Be mindful of blocking operations: If a goroutine blocks on an I/O operation, it will be paused and another goroutine will be scheduled to run. This can lead to inefficient use of resources if there are many goroutines waiting on I/O. Consider using non-blocking I/O or asynchronous I/O to avoid this issue.

Keep critical sections short: When multiple goroutines access shared data, it's important to keep critical sections short to minimize the risk of race conditions. Consider using locks or other synchronization primitives to protect shared data.

In summary, while it is possible to run a large number of goroutines with GOMAXPROCS(1), it's important to consider the potential performance issues, deadlocks and race conditions, resource limitations, and design considerations. It's recommended to carefully test and monitor the application to ensure that it is functioning correctly and efficiently.

Conclusion

In conclusion, managing concurrent workloads with Goroutines in Go can be a powerful and efficient way to process large amounts of data and improve application performance. However, it's important to consider the potential drawbacks and design considerations, such as increased complexity, resource consumption, synchronization overhead, deadlocks, and race conditions. By carefully managing the number of Goroutines, using channels for communication, being mindful of blocking operations, and keeping critical sections short, it's possible to create scalable, maintainable, and efficient applications with Go.

Contributing

At Dwarves, we encourage our people to read, write, share what we learn with others, and contributing to the Brainery is an important part of our learning culture. For visitors, you are welcome to read them, contribute to them, and suggest additions. We maintain a monthly pool of $1500 to reward contributors who support our journey of lifelong growth in knowledge and network.

Love what we are doing?

Check out our products

Hire us to build your software

Join us, we are also hiring

Visit our Discord Learning Site

Visit our GitHub